Fixed-income types can be a dour bunch, who see bad news in the best of times.

But even they haven’t been this skeptical about Wall Street’s rosy forecasts for U.S. economic growth in nearly a quarter-century.

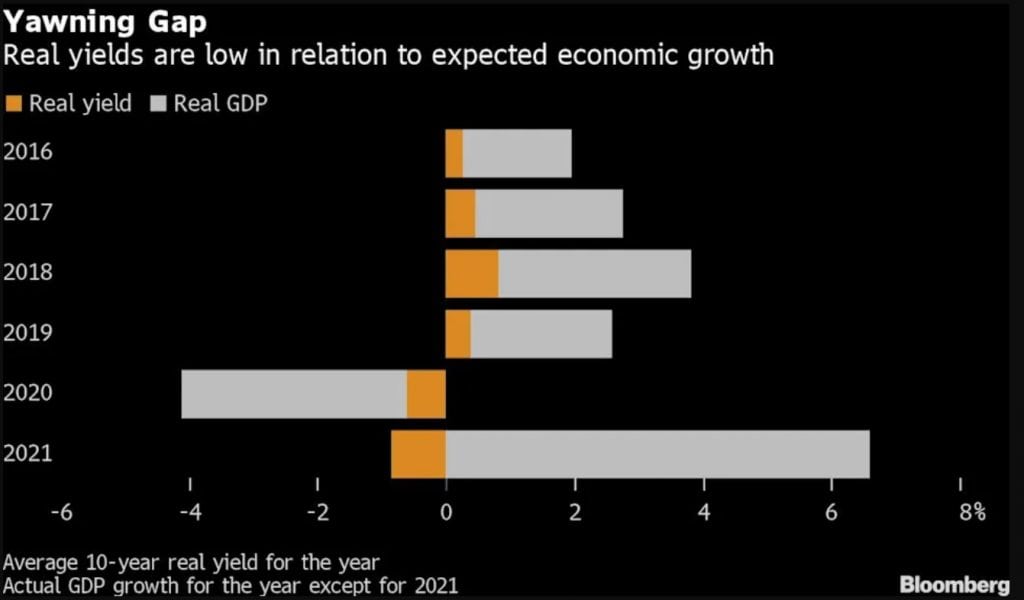

See, once you take inflation into account, it becomes clear that investors are willing to get paid nothing to hold onto ultra-safe U.S. Treasuries. In fact, so-called real yields, which strip out inflation expectations, are so low that they’re sending an ominous signal about the state of the economy that’s largely missing from all the bullish reopening forecasts.

Granted, some prognosticators downplay real yields as a pure read on growth simply because the Federal Reserve has distorted so many market signals with its unprecedented bond buying. But if the market’s view is right, the rebound from the Covid-19 devastation could prove short-lived, or at least less robust than many analysts anticipate, and all manner of long-term interest rates may head lower again.

Strategists like Dominique Dwor-Frecaut at research firm Macro Hive see good reason to be pessimistic. She sees a slowdown ahead in part as consumers are set to be squeezed by price increases that are outstripping wage gains, just as government pandemic relief ends.

“Growth is going to hugely disappoint this quarter,” said Dwor-Frecaut, who previously worked in the New York Fed’s markets group.

Ten-year U.S. real yields — as measured by the yield on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities — are around minus 0.9%. That’s roughly where they were in February, even as Wall Street forecasters have ramped up growth projections. The rate is only about a quarter-percentage point above record lows touched in 2020. In the five years before the pandemic, it averaged roughly 50 basis points.

The rate briefly surged last week. But it was mainly a result of inflation expectations tumbling on the Fed’s surprise hawkish policy shift, rather than an indication that investors were lifting their view on growth.

Simple Math

A negative real rate can be a hard concept to grasp. The Fed’s debt buying looms large, as it helps limit the upside for all yields. Nominal 10-year rates, for example, are around 1.5%, having failed to crack above 2% since 2019. Then subtract some of the highest inflation expectations in years — as measured by TIPS breakeven rates — and the resulting real rate is firmly below zero.

Of course, there’s a reason investors buy TIPS with negative yields. They can profit if consumer prices rise by a larger amount than breakeven rates currently price in, says Tim Magnusson, a portfolio manager at Garda Capital Partners LP. What’s more, they always have a positive coupon stream, since the minimum coupon rate on these securities is above zero.

But the bigger question is whether skeptical investors or economists’ rosier outlook will prevail in the months ahead.

Wall Street forecasters and independent research groups have been raising growth forecasts amid progress in the nation’s vaccination campaign. Gross domestic product will probably expand 6.6% this year, the fastest pace in decades, according to economists surveyed by Bloomberg. That projection has risen from 5.7% in March.

The gap between real yields and forecasters’ outlook for growth is the widest since TIPS debuted in 1997.

The optimism toward growth is understandable, given all the monetary and fiscal stimulus and pent-up spending filtering through the economy.

However, investors can point to warning signs. Retail sales declined in May, after a stimulus-related splurge the prior two months. And while spending is expected to rise further, the pace will probably moderate as enhanced unemployment benefits expire. Job creation in April and May was below consensus forecasts.

Shifting Approach

The Fed’s shift last week threw investors for a bit of a loop. For months, it had been signaling a new approach that allows price pressures to run hot as the economy recovers. But last week’s meeting seemed to indicate that officials’ willingness to let inflation rise may be more limited than most expected.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell on Tuesday said he saw the recent inflation uptick as transitory, and said the labor market has a long way to go and needs continued support.

Ten-year breakeven rates, which represent investors’ average expectations for consumer-price inflation for the next decade, tumbled last week after the Fed meeting, and then stabilized on Powell’s latest remarks. They’re now about 2.3%, down from an eight-year high in May of about 2.6%.

What could actually lift real rates — even if the path of growth remains uncertain — is if the Fed begins to taper its debt buying. Traders see growing odds that it may communicate that change at its annual symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming in August.

But for now these rates are stuck solidly below zero, showing that the bond market has yet to buy into the economy’s resurgence.

“Real rates are the market’s discounter of the future itself, and their low level is telling us something,” said Padhraic Garvey, head of global debt and rates strategy at ING Groep NV. “I still see deeply negative real yields as a menacing indicator that points to the risk for a bad outcome.”