What’s popular isn’t always what’s best for Social Security.

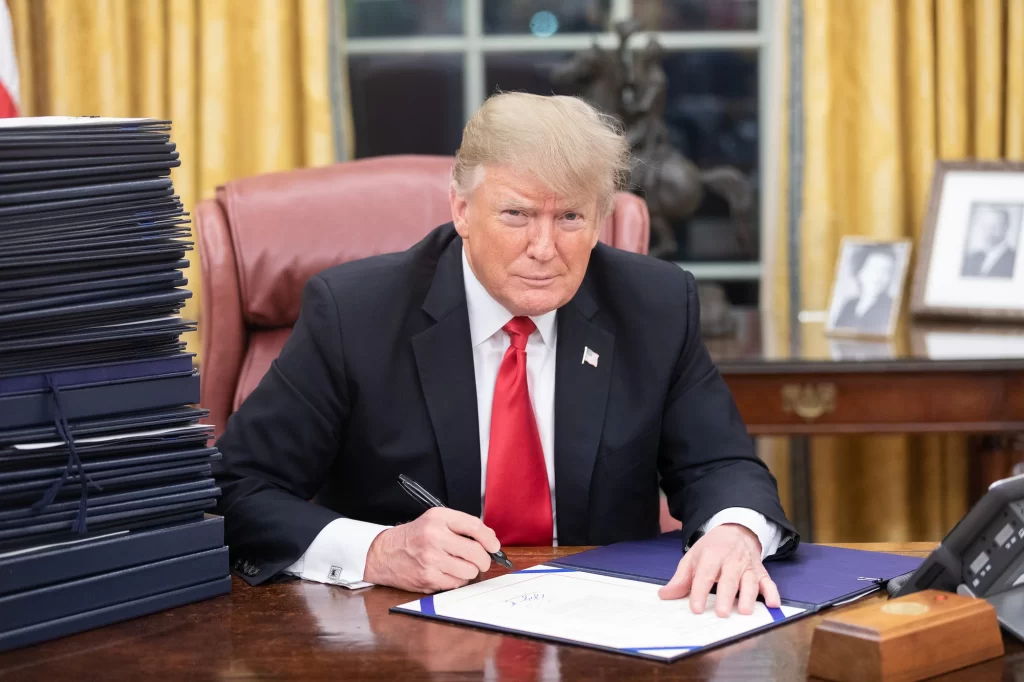

A little over a month ago, voters from across the country headed to the polls or mailed in their ballots to determine which presidential candidate would lead our nation forward for the next four years. Mere hours after the last polls closed, the Associated Press called the 2024 election in favor of former President Donald Trump.

In addition to Trump becoming the new president-elect, Republicans garnered enough seats to flip the Senate in their favor, as well as maintain a slim majority in the House of Representatives. In other words, Republicans have a unified government for the first time since Donald Trump initially took office in January 2017.

While there are a number of issues Trump and the incoming Congress will need to tackle once in office, perhaps none is more pressing than Social Security’s worsening financial foundation.

Social Security is contending with a $23.2 trillion (and growing) long-term funding shortfall

Ever since the first retired-worker benefit check was mailed out in January 1940, the Social Security Board of Trustees has issued an annual report that’s examined the then-current financial health of the program, as well as estimated its long-term solvency (i.e., the 75 years following the release of a report).

For the last 40 years, the Trustees Report has cautioned that Social Security’s long-term income collection would be insufficient to cover its outlays, which includes paying benefits and, to a far lesser degree, the administrative expenses associated with overseeing the program. Social Security’s long-term funding obligation shortfall has been consistently growing for decades and currently stands at an estimated $23.2 trillion.

To make matters worse, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund (OASI), which doles out monthly benefits to retired workers and survivor beneficiaries, is set to exhaust its asset reserves by 2033.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean Social Security is insolvent or in any danger of going bankrupt. More than 91% of the income Social Security collects comes from the 12.4% payroll tax on earned income — wages and salary, but not investment income. As long as this money is rolling in and workers are paying tax on their wages and salary, there will always be money to disburse to eligible beneficiaries.

But what is at stake is the ability to maintain the current payout schedule, including cost-of-living adjustments (COLA). Without reforms, sweeping benefit cuts of up to 21% may be necessary if the OASI depletes its asset reserves nine years from now.

While people on social media message boards are often quick to incorrectly blame “congressional theft” or “undocumented immigrants” for the cracks in Social Security’s financial foundation, the bulk of the blame lies with ongoing demographic shifts, which includes:

- Baby boomers leaving the workforce and weighing down the worker-to-beneficiary ratio

- Beneficiaries living considerably longer than when the first retired-worker check was mailed in 1940

- Rising income inequality, which has allowed more earned income to escape the payroll tax

- A historically low U.S. birth rate, which may further hamper the worker-to-beneficiary ratio

- A 58% decline in legal net migration into the U.S. since 1998

The OASI’s asset reserves are forecast to be exhausted by 2033. US Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund Assets at End of Year data by YCharts.

Donald Trump has a plan to change Social Security

While on the campaign trail prior to his election as president for a nonconsecutive second term, Trump pledged to protect Social Security, which is something every candidate does.

However, in late July, Trump provided specifics on one way he would look to change Social Security once in office. Posting on his social media platform Truth Social, Trump stated, “Seniors should not pay tax on Social Security.” In short, he wants to do away with the taxation of Social Security benefits.

In 1983, when Social Security’s asset reserves were nearly exhausted, Congress passed and President Ronald Reagan signed the Social Security Amendments of 1983 into law. This was the last major bipartisan overhaul of America’s top retirement program. It gradually increased the payroll tax and full retirement age for workers, as well as introduced the taxation of benefits.

Beginning in 1984, up to 50% of benefits could be taxed at the federal rate if provisional income (adjusted gross income + tax-free interest + one-half benefits) surpassed $25,000 for a single filer or $32,000 for a couple filing jointly. In 1993, under the Clinton administration, a second tax tier was added that exposed up to 85% of benefits to federal taxation if provisional income surpassed $34,000 for a single filer and $44,000 for a couple filing jointly.

What’s made this such a hated tax among seniors is that it’s never been adjusted for inflation. When it was introduced four decades ago, it was applicable to roughly 1 out of 10 households. But as COLAs have increased Social Security checks over time, an ever-increasing percentage of seniors are becoming subject to the taxation of benefits.

Trump’s thesis being that ending the taxation of Social Security benefits would put more money back into the pockets of seniors who’ve struggled to counter the effects of inflation. According to nonpartisan senior advocacy group The Senior Citizens League, the buying power of a Social Security dollar has declined by 20% since 2010.

With Republicans controlling Congress and President-elect Trump proposing a change that seniors would overwhelmingly support, the question has to be asked: Can this change become reality in 2025?

Trump’s effort to change Social Security will face two (likely) insurmountable headwinds

While public opinion undeniably favors shelving the taxation of benefits, two mammoth headwinds stand in the way of Trump amending the Social Security Act.

The first issue that the former president would have to overcome is justifying the elimination of one of Social Security’s three sources of income. As noted, Social Security generates more than 91% of its income via the 12.4% payroll tax. The remainder comes from a combination of interest income earned on its asset reserves, as well as taxing Social Security benefits.

If the taxation of benefits is removed, America’s leading retirement program would miss out on a lot of future income. Estimates from the latest Trustees Report show the taxation of benefits will provide a cumulative $943.9 billion in income from 2024 through 2033. If this income source is eliminated, it would expedite the timeline to the OASI’s asset reserve depletion date and potentially exacerbate the magnitude of benefit cuts needed to sustain payouts over the next 75 years.

To be blunt, what’s popular doesn’t always make fiscal sense. Despite the taxation of benefits being widely disliked by beneficiaries, there’s no financial incentive for lawmakers to get rid of it, or even adjust it for inflation, given Social Security’s widening long-term funding obligation shortfall.

The second headwind Trump is unlikely to be able to navigate is the 60 votes required in the upper house of Congress to amend the Social Security Act.

The last time either party held a supermajority of seats (60 or more) in the Senate was 1979. This means any amendments to America’s leading retirement program will require bipartisan support. Even if every Republican in the upper house agreed with Trump’s plan in 2025, seven Democrats would also need to support this proposal, which seems highly improbable.

While a unified Republican government may pave the way for personal and corporate income tax reforms, the taxation of Social Security benefits is almost certainly here to stay, with no changes expected in 2025.