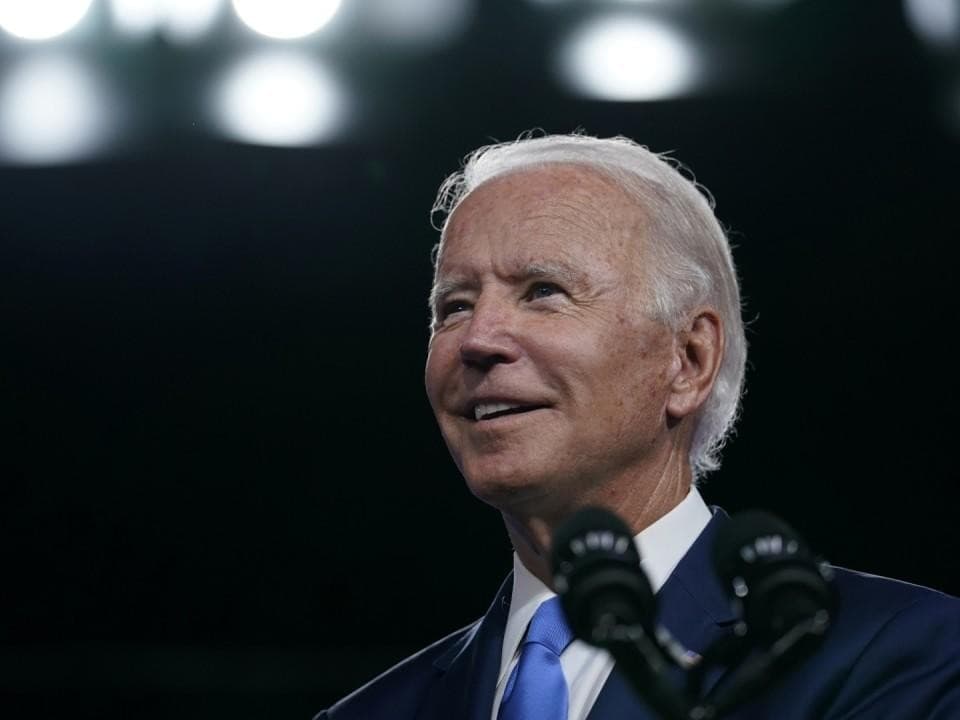

The Biden administration is ready to sell additional volumes of crude oil from the strategic petroleum reserve after the end of the 180-million-barrel release plan and then it would begin replenishing the SPR once prices fall to $67-$72 per barrel. This is the main outtake from a fact sheet published by the White House this week as the administration continues to look for ways to tame retail fuel prices with just weeks left until the midterm elections.

The SPR draws—and plans for more—have caused concern among some analysts, who have pointed out that the purpose of the SPR is not to keep gasoline prices under control but to ensure the country’s oil supply in an emergency.

Others have questioned the very relevance of the SPR in today’s oil world, where the United States is the biggest oil producer on the planet, but market reactions to this year’s SPR releases have suggested that keeping a strategic reserve is still quite a good idea.

The main concern among those watching SPR levels has been its replenishment. Because of the massive draws that the Biden administration implemented as a tool for keeping a lid on gasoline prices, inventories at the SPR are now at the lowest in almost 40 years, at some 405 million barrels.

“The Administration intends to repurchase crude oil for the SPR when prices are at or below about $67-$72 per barrel, adding to global demand when prices are around that range,” the White House said in a fact sheet this week.

It went on to add that “This repurchase approach will protect taxpayers and help create certainty around future demand for crude oil. That will encourage firms to invest in production right now, helping to improve U.S. energy security and bring down energy prices that have been driven up by Putin’s war in Ukraine.”

The above led some commentators in the media to suggest that Biden is effectively embracing the oil industry after spending most of the first two years of his term fighting it. Indeed, the fact sheet also noted the replenishment of the SPR would involve contracts that lock in prices for two to three years ahead.

If it looks like a price floor and it sounds like a price floor, it must be a price floor, as Energy Intelligence demonstrated in a detailed analysis of the replenishment target price range.

The analysis points out that the range mentioned by the administration is at about the same price level that motivates U.S. producers to hedge their future output. When oil goes higher than $70 a barrel, the authors explain, they prefer selling them on the spot market.

The range is also higher than the breakeven level for most producers, the analysis also points out, suggesting this could be an incentive for drillers to boost production steadily.

It makes sense, on the face of it. What producers or any commodity wouldn’t be glad to hear there will be demand for their product two or three years from now? Yet this is only on the face of it.

Before Biden suggested a price floor for oil, he targeted the U.S. oil industry with yet another call for a change of behavior. He told oil companies they should stop buying back shares and invest in production growth and fuel price control.

“My message to the American energy companies is this: You should not be using your profits to buy back stock or for dividends. Not now. Not while a war is raging,” the U.S. President said. “You should be using these record-breaking profits to increase production and refining.”

The U.S. oil industry has demonstrated more than once it is not really a huge fan of being told what to do, especially by someone who has effectively declared the industry the main obstacle to a better future for America.

But it has also demonstrated something else that few could have seen coming: restraint. The pandemic seems to have knocked the growth-at-all-costs mentality out of U.S. oil, and companies are now not only focusing on returning cash to shareholders but also being more pragmatic about production growth.

It bears noting that this new restraint is also related to Biden administration policies. The focus of these is entirely on the transition from fossil fuels to alternative sources of energy. In other words, the Biden administration is betting on the death of oil. It really shouldn’t be surprising when oil producers don’t want to help it bring prices down in time for the midterms.

All of this, however, does not really solve the problem of a dwindling strategic oil reserve. Because nobody really expects oil prices to fall to $72 any time soon. If anything, they are likely to rise further in a couple of months when the EU embargo on Russian oil kicks in.

And since the EU has signaled its plans to stay the course with anti-Russian sanctions for the observable future, prices may remain elevated for an extended period of time, making the replenishment job of the U.S. administration rather difficult, even as U.S. oil production is expected to return to record levels in 2023.