Consider the headline or TV-screen-crawl you’ve seen (a lot) since the October consumer price index hit the news. It said something like: “Inflation Hits 30-year High, Democrats Doomed.”

Year over year, things cost 6.2% more this October than last, and the steepest increases were for food and energy — especially energy. Gas prices proclaim their ascent high in the air over street corners everywhere.

Economists may know (and even agree) that the current inflation is attributable to the pandemic and its aftermath: sluggish supply chains, reluctant workers, shortages and interrupted energy deliveries. We also know the government has mainlined trillions of dollars in buying power to consumers since the spring of 2020. Price hikes might be considered all but inevitable.

But one of the lessons from inflationary eras past is that voters are less interested in causal responsibility than in forcing a change. In other words, if you are in office now, you are holding the bag.

Public polling has consistently found widespread alarm: Morning Consult, for example, reported this week that 87% of Americans were “concerned about rising prices.”

As such numbers go up, the approval numbers for President Biden and his party predictably go down — especially where they had already been falling due to COVID spikes, vaccine controversies and the ugly exit from Afghanistan.

The Quinnipiac poll released Thursday found a plurality (46%) of Americans wanted Republicans to take back control of Congress next year.

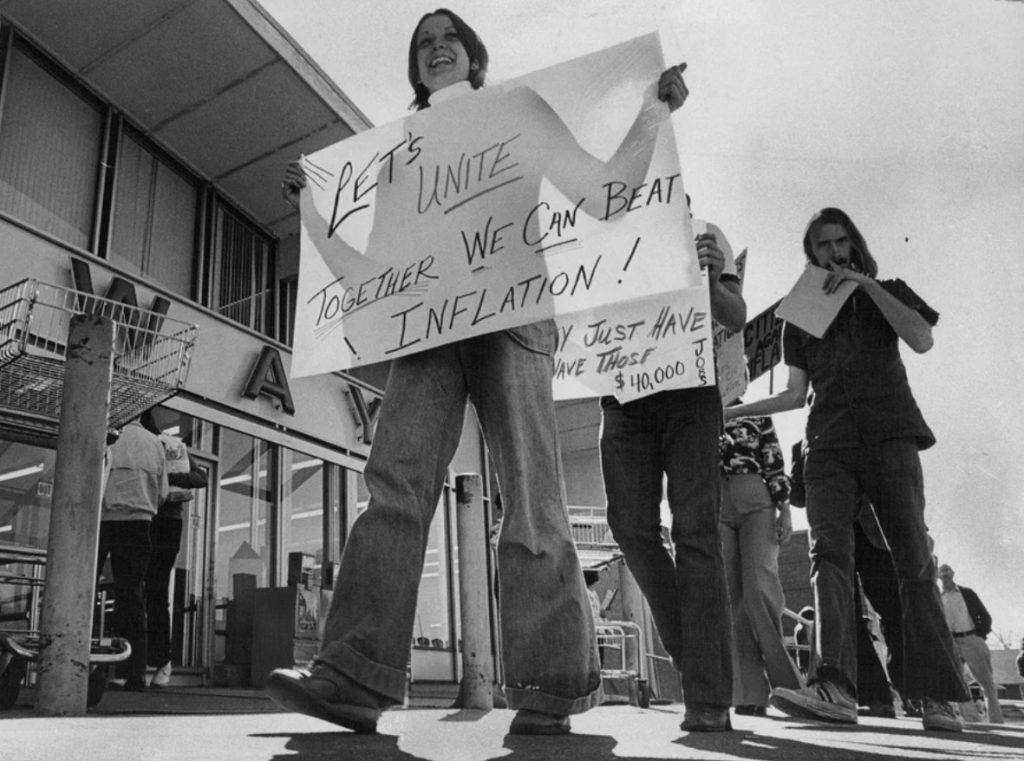

Flashback: That ’70s Scourge

When the October price numbers came out, many of us in the killjoy business dredged up our dreariest memories to support our direst prognoses. It’s been a while, but we remember how inflation ravages the economy, sours the national mood, and poisons the electoral prospects of a president and his party.

And we could scarcely wait to share our memories of that decade not so distant when “stagflation” — sluggish growth with high unemployment and high inflation by rising prices — was defeating the best efforts of government at every turn.

Flashback to the 1970s, when people still used the word flashback a lot. The decade began with Richard Nixon in the White House juggling the Vietnam War, a realignment of the global superpowers called “détente” and his own reelection campaign.

With all that, reports biographer John A. Farrell, Nixon was “increasingly anxious” about something else — the inflation driven by government spending for the Vietnam War and the social programs of the 1960s.

Nixon knew the three biggest inflation spikes of the 20th century had followed the two world wars and the war in Korea in the early 1950s. He had also watched the consumer price index rise 5.5% in his first year in office and 5.8% in his second.

Responding to this trend, the Federal Reserve Board had begun gradually tightening the money supply. Nixon believed those moves had caused too much economic pain and hurt Republican candidates for Congress in the 1970 midterms.

The word “stagflation,” the double whammy of stalled growth amidst higher prices, was already in use in the White House.

Nixon makes his move

So in August 1971, Nixon used a special authority recently granted him by Congress to impose wage and price controls. While temporary, and arguably counterproductive in the long run, Nixon’s controls helped hold inflation to 3% in 1972, his reelection year.

But if everything came together for Nixon in 1972, it largely fell apart immediately thereafter. The Watergate burglary he had tried to cover up was exposed and began to dismantle his administration. And after Nixon’s wage-price controls expired, the CPI nearly doubled in 1973 and almost doubled again the year after, reaching double digits for the first time since the immediate aftermath of World War II.

At this point, the monster of inflation was joined by an ally, the Arab embargo that scrambled the global market for oil. Led by Saudi Arabia, the Arab oil producers fighting yet another war with Israel cut off exports to the U.S. and other countries that backed Israel in the 1973 “Yom Kippur war.”

Virtually overnight, the global market price of oil soared from about $3 a barrel to $12 (more than $70 in 2021 dollars). If you could find a station that had gas, you paid four times as much as before to pump it.

Even though the embargo ended after six months, prices stayed high, and the “first oil shock” set a pattern that would outlast the decade.

All this was happening just as the Watergate scandal was playing out in Congress and the courts, sending Nixon’s approval rating to historic lows as he faced impeachment (he resigned in August 1974).

Ford whiffs with WIN

Nixon was replaced by his genial but uncharismatic vice president, Gerald Ford. Standing before a joint session of Congress in October 1974, Ford wore a red button with the letters WIN in white. He told the Congress, and a national TV audience, that the letters stood for “Whip Inflation Now.”

He urged Americans to carpool, turn down the thermostat and plant a WIN garden. Pledge to your part, he said, and the White House would send you a button like the president’s. (Economic adviser Alan Greenspan went along at the time but later wrote he considered the campaign “incredibly stupid.”)

Ford’s cheery effort achieved little, and overall inflation peaked above 12% and averaged nearly 9% during the years of his presidency. It was not the only albatross Ford bore as a candidate in the election of 1976, but it may well have been the heaviest. Americans might forgive him for pardoning Nixon, but they could not ignore the staggering increases in prices for gas and a host of other everyday purchases. Inflation, in the end, whipped another president.

Carter’s choice

Ford gave way to President Jimmy Carter, who knew well what inflation had contributed to his taking up residence in the White House, but his first choice as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board was wary of high interest rates taking down the economy, and Carter was hamstrung by an energy crisis and a host of other conflicts. The midterm elections in 1978 were brutal for Carter’s Democrats.

By Carter’s third summer in office, the Iran revolution had led to a second oil shock sending the price of gas higher than ever for legions of drivers waiting in long lines. That put yet another log on the inflation fire, which was soon burning as hot as ever.

At that point, Carter found his his dragon-slayer in the tall, balding and bespectacled Paul Volcker, whom he made chair of the Fed. Having warned Carter bluntly he would do so, Volcker used his power to raise interest rates within the banking system — a cost of money soon passed on to borrowers at all levels.

Interest rates soon blew past 10% and well into uncharted territory. The effect was to burden investment and clobber economic growth. Businesses cut back and millions of Americans lost their jobs.

Painful as it was, Volcker believed only such frontal confrontation could wring inflation out of a free market economy. Otherwise, expectations of higher prices became a major cause of those very increases. So in Carter’s reelection year of 1980, inflation and interest rates were both in double digits and the unemployment rate had climbed back up to nearly the level in Ford’s last year.

In his 900-page compendium of Carter’s presidency, his former domestic policy adviser Stuart Eizenstat wrote that the president, “fully aware that he was putting his own election at great risk, set in motion the successful battle against the ruinous inflation of the 1970s…by appointing Paul Volcker and giving him free rein.”

Enter Reagan, eventual beneficiary

Like Ford four years earlier, Carter had other things to answer for in seeking reelection — not least the crisis in Iran where U.S. embassy staff had been held hostage for a year. But like his predecessor, Carter found inflation quite possibly the most vexing of his political liabilities. His opponent, Republican Ronald Reagan, asked voters in his debate with Carter if they felt “better off than four years ago.” They didn’t, and Reagan won an Electoral College landslide.

The hostages were freed by Iran the day Carter left office, but the rest of the hangover from the 1970s lingered far longer. Unemployment reached 10% for the first time since the Depression, while the cost of loans for homes and businesses reached unprecedented levels.

Volcker stuck to his guns. And Reagan stood by Volcker, reappointing him in 1983 when interest rates and their political costs were still running high. Reagan had endured a rough 1982 midterm election that cost him 25 seats in the House and prompted talk of him as a one-term president.

But as Volcker was beginning his second term, his persistence had begun to bear fruit. Inflation rates came down in 1983 and again in 1984. Volcker eased interest rates accordingly and Wall Street and Main Street took heart and began hiring more workers. Reagan won a second term in 1984 with 60% of the popular vote and 49 of the 50 states in his column.

Inflation tame since then

Recent attention has been focused on the 6.2% CPI jump for October, which we repeat often is the sharpest increase in 30 years. What happened 30 years ago, and why does that stand out so much?

In 1990 Iraq invaded its oil-rich neighbor Kuwait, disrupting the global oil market and destabilizing the Persian Gulf region. President George H.W. Bush declared “this cannot stand” and organized an international coalition to push the Iraqis out. This was when most Americans first heard the name of the Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein.

Early in 1991, Bush’s coalition drove the Iraqis out, advanced briefly into Iraq and then withdrew. But the 1990-91 Persian Gulf conflict in general contributed to a global recession that was felt in the U.S. Historians will debate how much this contributed to Bush’s defeat in the three-way presidential election of 1992. But inflation itself was not a factor, having declined to just 3% for the election year.

Thereafter, inflation remained in its cage long enough to be largely forgotten. In a 2020 article published by the Brookings Institution, Sage Belz and David Wessel cataloged several explanations for the decades of calm on what had been such a stormy sea.

They noted that central banks had prioritized fighting inflation for a generation, and that labor-management power shifts had reduced pressure for wage hikes. They also cited the expansion of trade and supply systems often referred to as globalization, and the use of technology to increase price-setting efficiency of modern companies.

But they also emphasized that periods of high inflation in the past had led various economic actors to assume higher prices and higher inflation, a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy that typically defeated anti-inflation campaigns. The lesson of the Volcker years was that such presumption can be hard to eradicate.

In any event, since 1984 (the middle of Volcker’s time as chairman), only one president has had to deal with inflation of even 5% (Bush in 1990), and in that case it was only that high for one year.

We will see if Biden breaks that skein, of course, and whether that breaks Biden.