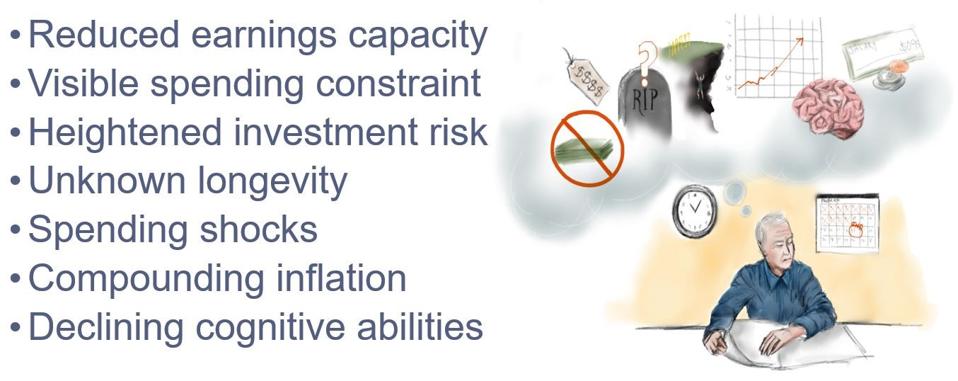

It is important to understand from the very outset how changing risks are primarily what separate retirement income planning from traditional wealth management. Retirees have less capacity for risk, as they become more vulnerable to a reduced standard of living when risks manifest. Those entering retirement are crossing the threshold into an entirely foreign way of living. These risks can be summarized in seven general categories, listed in Exhibit 1.1.

Exhibit 1.1 – Retirement Risks

Reduced earnings capacity

Retirees face reduced flexibility to earn income in the labor markets as a way to cushion their standard of living from the impact of poor market returns. One important distinction in retirement is that people often experience large reductions in their risk capacity as the value of their human capital declines. As a result, they are left with fewer options for responding to poor portfolio returns.

Risk capacity is the ability to endure a decline in portfolio value without experiencing a substantial decline to the standard of living. Prior to retirement, poor market returns might be counteracted with a small increase in the savings rate, a brief retirement delay, or even a slight increase in risk taking. Once retired, however, people can find it hard to return to the labor force and are more likely to live on fixed budgets.

Visible spending constraint

At one time, investments were a place for saving and accumulation, but retirees must try to create an income stream from their existing assets—an important constraint on their investment decisions. Taking distributions amplifies investment risks by increasing the importance of the order of investment returns in retirement.

It can be difficult to reduce spending in response to a poor market environment. Portfolio losses could have a more significant impact on the standard of living after retirement, necessitating greater care and vigilance in response to portfolio volatility. Even a person with high risk tolerance (the ability to stomach market volatility comfortably) would be constrained by his or her risk capacity.

The traditional goal of wealth accumulation is generally to seek the highest returns possible in order to maximize wealth, subject to risk tolerance. Taking on more risk before retirement can be justified because many people have greater risk capacity at that time and can focus more on their risk tolerance. However, the investing problem fundamentally changes in retirement.

Investing during retirement is a rather different matter from investing for retirement, as retirees worry less about maximizing risk-adjusted returns and worry more about ensuring that their assets can support their spending goals for the remainder of their lives. After retiring, the fundamental objective for investing is to sustain a living standard while spending down assets over a finite but unknown length of time. The spending needs that will eventually be financed by the portfolio no longer reside in the distant future. In this new retirement calculus, views about how to balance the trade-offs between upside potential and downside protection can change. Retirees might find that the risks associated with seeking return premiums on risky assets loom larger than before, and they might be prepared to sacrifice more potential upside growth to protect against the downside risks of being unable to meet spending objectives.

The requirement to sustain an income from a portfolio is a new constraint on investing that is not considered by basic wealth maximization approaches such as portfolio diversification and modern portfolio theory (MPT). In MPT, cash flows are ignored, and the investment horizon is limited to a single time period such as a year. This simplification guides investing theory for wealth accumulation. When spending from a portfolio, the concept of sequence-of-returns risk (the order that market returns arrive) becomes more relevant, as portfolio losses early in retirement will increase the percentage of remaining assets withdrawn to sustain an income. This can dig a hole from which it becomes increasingly difficult to escape, as portfolio returns must exceed the growing withdrawal percentage to prevent further portfolio depletion. Even if markets subsequently recover, the retirement portfolio cannot enjoy a full recovery. The sustainable withdrawal rate from a retirement portfolio can fall below the average return earned by the portfolio during retirement.

Heightened investment risk

As we just discussed, retirees experience heightened vulnerability to sequence-of-returns risk when they begin spending from their investment portfolio. Poor returns early in retirement can push the sustainable withdrawal rate well below that which is implied by long-term average market returns.

The financial market returns experienced near the retirement date matter a great deal more than retirees may realize. Retiring at the beginning of a bear market is incredibly dangerous. The average market return over a thirty-year period could be quite generous, but if one experiences negative returns in the early stages when spending begins, withdrawals can deplete wealth rapidly, leaving a much smaller remainder to benefit from any subsequent market recovery, even with the same average returns over a long period of time. What happens in the markets during the fragile decade around the retirement date matters a lot.

The dynamics of sequence risk suggest that a prolonged recessionary environment early in retirement without an accompanying economic catastrophe could jeopardize the retirement prospects for particular groups of retirees. Some could experience much worse retirement outcomes than those retiring a few years earlier or later. It is nearly impossible to see such an instance coming, as devastation for a group of retirees is not necessarily preceded or accompanied by devastation for the overall economy.