NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover may have just captured a snapshot of the Red Planet’s long-ago Great Drying.

Curiosity has detected relatively high levels of sulfate salts in the rocks of Gale Crater, a new study reports. Gale hosted a lake-and-stream system in the ancient past, and the newfound salts were likely concentrated by evaporation during a period of low water levels, researchers said.

This period may have been part of a normal cyclical fluctuation, a regular climatic change perhaps driven by recurring shifts in Mars’ axial tilt or orbital parameters. “Alternatively, a drier Gale lake might be a sign of long-term, secular global drying of Mars, posited based on orbital observations,” the scientists wrote in the new study, which was published online today (Oct. 7) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

A planet transformed

Mars was once a relatively warm and wet world, complete with rivers and lakes and, most researchers believe, an ocean covering a large swath of the planet’s northern hemisphere.

But things began to change around 4.2 billion years ago. Mars lost its global magnetic field, which had protected the planet’s atmosphere from the solar wind, the stream of charged particles flowing continuously from the sun.

As a result, Mars lost the vast majority of its air to space by about 3.7 billion years ago, causing the planet to become much colder and drier. Today, Mars’ air is just 1% as dense as Earth’s atmosphere at sea level. (Luckily for us, Earth still has its global magnetic field.)

The Curiosity rover is helping scientists better understand the Red Planet’s history, including its dramatic transformation.

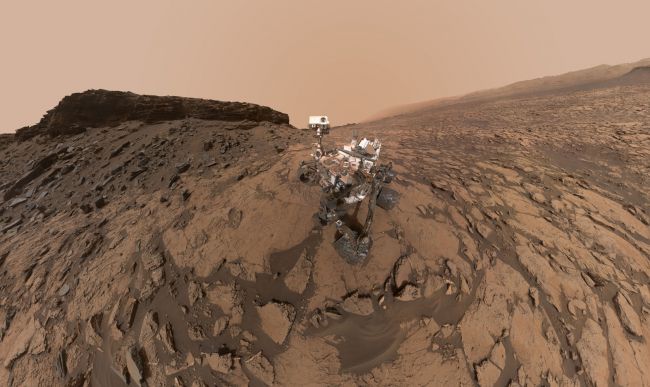

The car-size rover landed inside the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater in August 2012, tasked primarily with assessing the area’s past habitability. Curiosity quickly found lots of evidence of long-ago liquid water. Indeed, the mission team has determined that Gale’s floor is an ancient lake bed, and that the area could have supported Earth-like life for long stretches — perhaps hundreds of millions of years at a time — in the ancient past.

In September 2014, Curiosity reached the base of Mount Sharp, the bizarre, 3.4-mile-high (5.5 km) mountain that rises from Gale’s center. The rover has been climbing the mountain’s foothills ever since, examining younger and younger sediments as it goes. And that brings us to the new study.

A salty crater lake

The researchers analyzed measurements Curiosity made while exploring the upper Murray Formation, an assemblage of exposed sedimentary rock near Mount Sharp’s base thought to be 3.3 billion to 3.7 billion years old.

They found that these rocks are strongly enriched in sulfate salts — much more so than the deposits Curiosity had previously examined on the crater floor. (Those older rocks indicated an aqueous environment with water so fresh it was probably drinkable, mission team members have said.)

“Bulk enrichments” of calcium sulfate are widespread through about 500 feet (150 m) of the Murray Formation, the new study reports, while nuggets of high magnesium sulfate concentration speckle a thinner section of rock layers.

These salts were probably deposited along the margins of the Gale Crater basin, where the water was shallow. The deposits may trace back to multiple ponds on the fringes of the central lake, the researchers said.

Still, these salty ponds may have been habitable, the researchers added, noting that hypersaline lakes here on Earth teem with life. Indeed, the nature of the detected salts is intriguing from an astrobiological point of view.

“Sulfur is a basic element for life,” study lead author William Rapin, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, told Space.com. “And we show that there was sulfate available in the water.”

Solving the mystery

It’s possible that the Gale Crater lake system was drying out for good around the time these salty deposits were laid down, Rapin said.

“Maybe habitable environments had started to become niche,” he said. “Maybe large regions of Mars were already too arid.”

But there’s also that other possibility — that Mars was in a temporary dry spell but would become wet again when its axis of rotation, or its orbital eccentricity, changed.

Curiosity’s work could soon help solve this mystery. Mars orbiters have detected sulfate salts higher up on Mount Sharp. Curiosity is making its way toward those deposits and should start encountering them in the next year or two, if all goes according to plan, Rapin said. (The newfound salt deposits were not spotted by Mars orbiters.)

What the rover finds there, and along the way, should help researchers piece together the evolution of the Gale Crater lake system, he added.

“We know we’re going to have an answer — maybe a big answer — about what happened next, including with the sulfate deposits, in the years to come,” Rapin said.