A nuclear battery powered by radioactive decay rather than chemical reactions could last for decades. The most efficient design yet may bring this concept closer to reality.

Researchers have wanted to use radioactive atoms to build exceptionally long-lasting and damage-resistant batteries since the 1900s. While some prototypes have been assembled and even used in space missions, they were not very efficient. Now Shuao Wang at Soochow University in China and his colleagues have improved the efficiency of a nuclear battery design by a factor of 8000.

They started with a small sample of the element americium, which is usually considered to be nuclear waste. It radiates energy in the form of alpha particles, which carry lots of energy but quickly lose it to their surroundings. So the researchers embedded americium into a polymer crystal that converted this energy into a sustained and stable green glow.

Then they combined the glowing americium-doped crystal with a thin photovoltaic cell, a device that converts light to electricity. Finally, they packaged the tiny nuclear battery into a millimetre-sized quartz cell.

Over 200 hours of testing, Wang says, the device produced a stable supply of electricity at a relatively high energy with unprecedented efficiency – and it only needed minimal amounts of radioactive material to function. Although americium has a half-life of 7380 years, the nuclear battery should run for several decades, because the components surrounding the sample will eventually be destroyed by the radiation.

Michael Spencer at Morgan State University in Maryland says the new battery has “much improved overall conversion efficiencies and output power” compared to past designs. However, it still produces much less power than conventional devices. It would take 40 billion of them to power a 60-watt light bulb, for instance.

The researchers are already working on improving their design’s efficiency and power output. They also want to make it easier and safer to use, since it contains possibly dangerous radioactive materials.

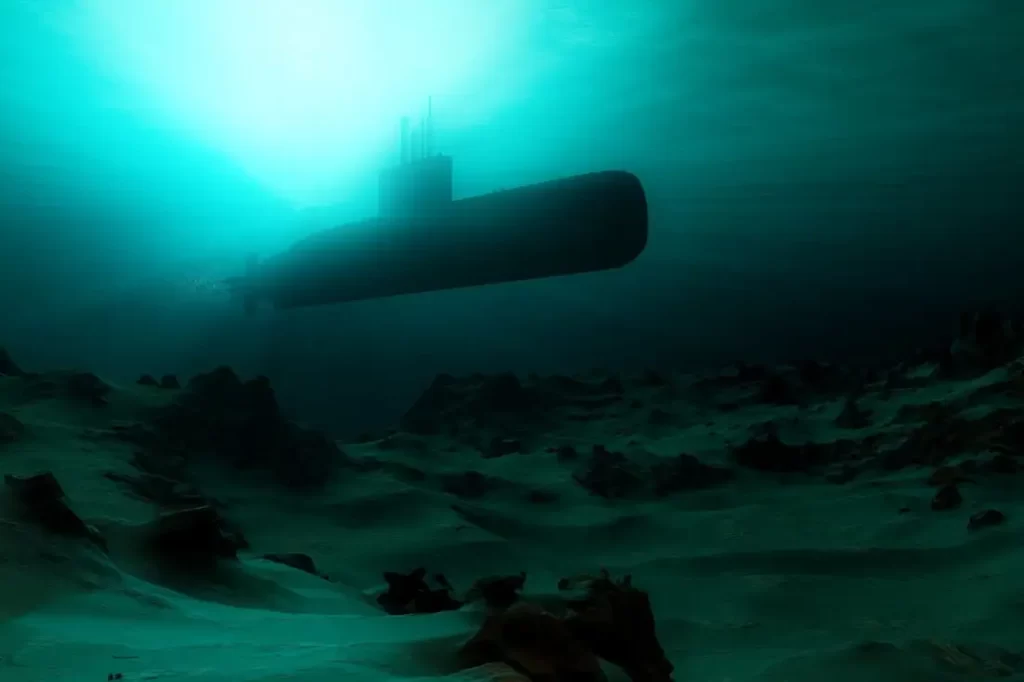

“Ideally, we envision our micronuclear battery being used to power miniature sensors in remote or challenging environments where traditional power sources are impractical, like deep-sea exploration, space missions or remote monitoring stations,” says Wang.