World financial leaders are pushing to overhaul a system for sovereign debt restructurings that has left poor countries locked out of capital markets as China’s emergence as a key player upends traditional negotiations.

How to fix the so-called common framework initiative, hatched during the pandemic to help poor countries rework their debt, was among the top issues debated during International Monetary Fund’s spring meetings, which just wrapped in Washington DC.

Leaders from the IMF and G-20 countries — which started and oversee the process — have made some fixes aimed at speeding up debt restructurings, which have left countries stranded in default for years amid protracted negotiations. Zambia, considered a “guinea pig” for the new model, only recently struck a deal with creditors, three and a half years after it defaulted. Ghana and Ethiopia, which stopped paying bondholders in late 2022 and 2023, respectively, are still negotiating.

“The last four years have been nothing short of a debt disaster,” said United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. He railed against the system’s perceived ineffectiveness, citing the example of Zambia. “This is more than counter-productive. This is immoral. This is wrong. This must change.”

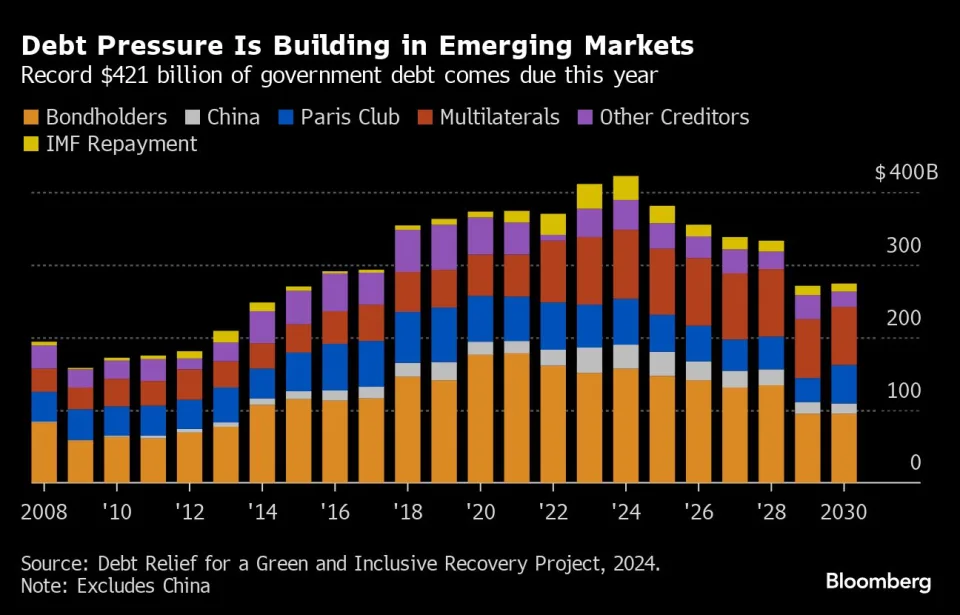

While defaults are expected to subside and risk premium for high yield countries has plunged, emerging-market governments — excluding China — face an estimated $421 billion in debt payments this year. That, combined with the risk aversion roiling markets amid tensions in the Middle East and the Federal Reserve’s higher-for-longer stance, is adding to the urgency to find a fix.

“Ultimately, the ones paying the real price of prolongated default periods are the people of these countries,” said Joe Delvaux, a money manager in London at Amundi SA. “For investors, the recoveries take longer to materialize, as the defaulted bonds will continue to trade at heavily discounted prices.”

Debt reworking has always been a complicated business that involves deals with the IMF, foreign Treasuries and private investors. Commercial banks and foreign governments, who traditionally held the lion’s share of defaulted debt, organized into the London Club and Paris Club of creditors, respectively, to streamline negotiations.

But now they’re being muscled out of talks by Wall Street and China, who as holders of more than half of defaulted debt have power to reject deals.

The common framework sought to guarantee each creditor group shared the burden evenly — meaning bondholders would take roughly the same losses as, say, Chinese banks. But each group negotiates separately, with little insight into the deal others are working on, making the process opaque.

“Give me a group of 10 people and two hours and we could come to an agreement,” said David Grigorian, a former IMF and World Bank economist. “Instead, we have this whole circus of everyone negotiating in different rooms.”

In limbo

In the case of Zambia, China last year rejected a proposed deal the African nation had reached with bondholders, delaying a resolution until February. Finance Minister Situmbeko Musokotwane said that the process showed the need to establish clearer timeframes within the framework, but defended the decision to deploy it rather than try to cut bilateral deals with each of its many creditors.

Read More: Zambia’s Musokotwane Sees Commercial Creditor Deal In Months

“We have no regrets,” he said in an interview Tuesday, noting that using the common framework it helped to remove suspicions among lenders that Zambia might cut a better deal for some that left others worse off.

Not everyone agrees.

“The single biggest criticism that we have as creditors is that the comparability of treatment is a joke,” Kevin Daly, a portfolio manager at Abrdn Investments Ltd. in London said of the common framework. “In reality, we’re getting a worse deal on Zambia and we’re gonna get a worse deal on Ghana.”

Turning point

Measures announced Tuesday may mark a turning point in the campaign to incorporate China into the system for restructuring some of more than $1.1 trillion in debt owed to Beijing by poor countries.

One of the main changes would be to allow the IMF to lend to countries even if negotiations with creditors are ongoing as long as there is progress toward a deal. Previously, a finalized agreement was needed before loans could be disbursed.

“The idea is that in the future the IMF can lend earlier once a country’s creditors have agreed to negotiations over the restructuring of official debt,” said Martin Muhleisen, a former director at the IMF’s key strategy, policy and review department who’s now a fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Risk Premium

After a bumpy few years, encouraging signs have emerged in the distressed debt world. Along with Zambia, countries like Suriname reached deals with creditors, sub-Saharan nations that had been locked out of borrowing for years issued debt and the risk premium for high-yield countries fell to a two-decade low.

The average premium that investors demand to hold African debt over US Treasuries was about 610 basis points as of Monday, according to JPMorgan indexes, down from more than 1,000 a year ago, a threshold that many investors consider an indication of distress.

Still, any changes made now would only apply to new debt reworks. And a lingering concern is that with China in the mix, the restructurings are providing repayment delays rather than write-offs. That risks leaving countries unable to pay years down the line.

The strategy amounts to “extend and pretend,” said Mark Sobel, a former US Treasury Department official who spent almost two decades focused on international policy, especially the IMF. “You don’t necessarily give the amount of debt relief the country needs to deal with overhangs.”