It may seem strange to be worried about inflation in the midst of a global recession, a pandemic and huge political ructions in the U.S., but I strongly suspect that it’s about to pick up both soon and sharply. How fast this happens depends on how quickly the developed world recovers over the next few months, but pressures are building. As has been the case for many years, global inflation has “Made in Asia” stamped all over it. This time, though, that’s likely to be compounded by much greater supply constraints in the economy.

First, a little humility. Forecasting inflation is fiendishly hard. Generally, the best forecast is what inflation is at the moment. Central banks have been neither good at forecasting inflation nor creating it. This is because, in essence, classical economics largely assumes that, all things being equal, increasing the supply of money pushes inflation higher. And yet, after years of rate cutting, quantitative easing and so forth, the only thing that has gone up is asset prices. It has been Apple Inc., as it were, not apples.

Clearly, then, not all things are equal. Economic models assumed that how quickly money changes hands (its velocity, in the jargon) is both stable and predictable. Instead, it has collapsed. That’s why all those people who predicted a massive rise in inflation as a result of central bank QE have been wrong. Velocity may pick up — your guess is as good as mine — but that wouldn’t tell us much about what happens in the next couple of years as it’s more of a long-term indicator. And there are signs aplenty that inflation is headed higher.

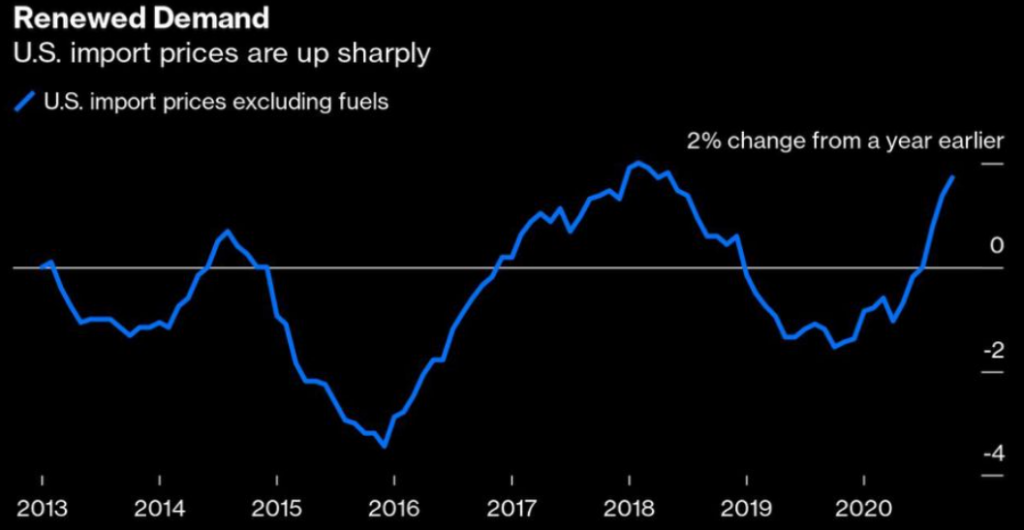

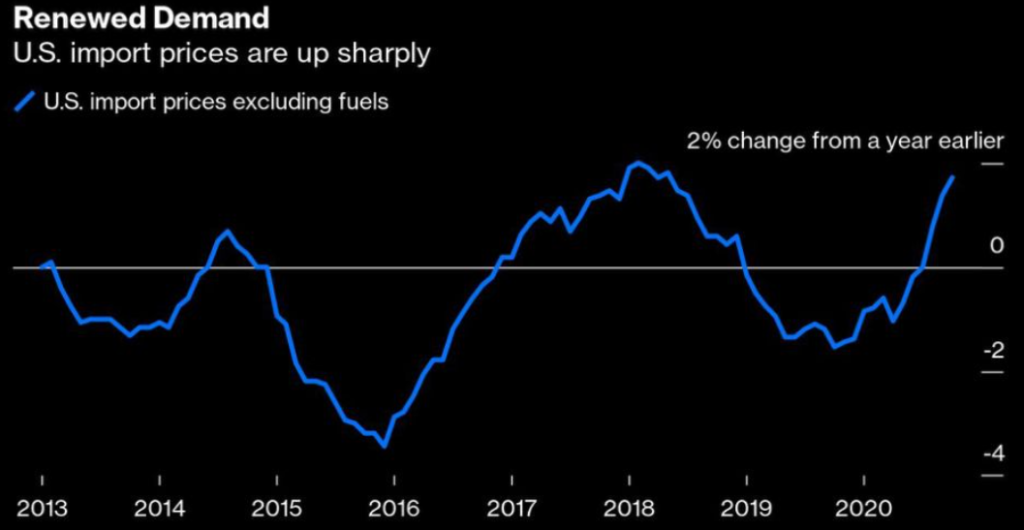

Ask yourself the following counterfactual. Had you known that the developed-world economy would be largely shut down, what would you have expected to happen to the prices of traded goods? Probably, you’d have expected them to collapse. But as the chart below shows, they didn’t even fall as much as in the manufacturing recession of 2015, let alone during the global financial crisis.

Prices are now rising strongly, in part because Asian growth is humming. Chinese export prices have risen year over year. Excluding oil, industrial commodity prices are also now higher than they were at the end of last year. Even if nothing moves between now and late spring of 2021, year-over-year comparisons will start to look very dramatic — as prices this spring were at their low point. These trends are already making themselves felt in the developed world. U.S. import prices, for example, are rising strongly. Durable goods prices are on a tear. There are signs that services inflation is also rising.

Yet much of the developed world is still in the midst of a pandemic, subduing demand. When the vaccine comes or the virus blows itself out, demand will pick up smartly. What will happen to prices when it does? I strongly suspect that a lot of manufacturing capacity has been lost. Both domestically and internationally, transportation is at once more difficult and more expensive. The vogue for ESG investments has probably also meant a lack of investment in stuff you dig out of the ground or drop on your foot.

Assuming that all this takes a fairly long time to get up and running, you would expect these constraints to last. The same is probably true of services. A lot of companies have already been put out of business and many more are likely to go to the wall. There has been, then, severe losses to economies’ supply potential. All of which means that the path of least resistance when demand picks up is higher prices.

How central banks react is key. They have told us that they will let economies run hot. What they’re really saying is that nothing they’ve done has made the slightest difference to overall inflation and they don’t know why. Still, let’s take them at their word. What would it mean in practice? Would they avoid putting up short rates or try to hold down long rates at a time when government borrowing is likely to remain huge? Either would, in effect, loosen monetary policy by driving real rates down when economies — and inflation — are growing strongly. This is not credible and countries that do nothing would probably see their currencies fall instead, thereby pushing imported inflation higher.

I suspect that private holders of longer-dated bonds won’t wait for central banks to change their minds, knowing that they’ll have to hike at some point. The risk is asymmetric. Bond yields are breathtakingly low and sooner or later they will rise, possibly rapidly: There is a lot of leverage in fixed income, and bonds with de minimis coupons potentially move a lot more in price than those that actually pay a decent rate of interest.

Those with a few grey hairs will remember the bond carnage of 1994. At some point, I’d expect yield curves to steepen dramatically from today’s levels. Avoiding longer-dated government and corporate debt and keeping to the very short end seems sensible. As would buying out-of-the-money, long-dated put options on long-dated debt.

Central banks have suppressed volatility and rates in debt markets for years. This is about to become much harder.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Richard Cookson was head of research and fund manager at Rubicon Fund Management. He was previously chief investment officer at Citi Private Bank and head of asset-allocation research at HSBC.