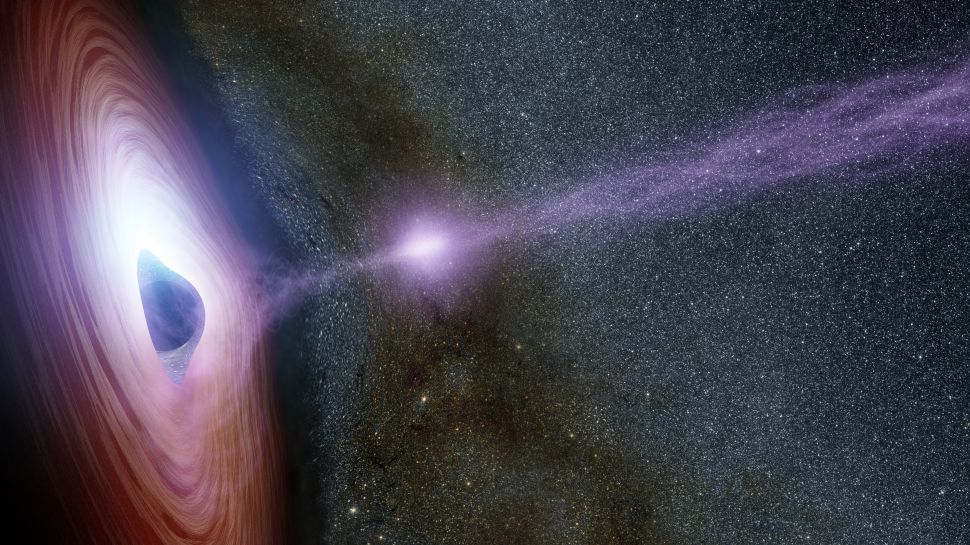

A black hole located 55 million light-years from Earth was recently the first to be captured in a close-up image. In another first, it received a name that’s a lot more interesting than the ones that usually identify black holes.

The new name, “Pōwehi,” means “embellished dark source of unending creation” in the indigenous Hawaiian language, and it was selected by Larry Kimura, a Hawaiian language professor at the University of Hawaii, Hilo (UH), according to a statement released by the university on April 10.

Kimura chose the name in collaboration with astronomers at two Hawaiian observatories that participated in the Event Horizon Telescope project (EHT), the international collaboration that produced the new image of the black hole. The Hawaiian words “pō” and “wehi” describe concepts in ancient chants related to the creation of the Hawaiian universe, UH representatives said.

“Embellished dark source of unending creation” is certainly more evocative than the name commonly used for this black hole (or, indeed, any black hole). Located at the heart of the galaxy Messier 87 (M87), the black hole in the image is generally called “M87’s black hole,” or “M87*,” with the asterisk at the end indicating that it’s the center of the galaxy, experts told Live Science.

Other names for M87* are also ho-hum strings of letters and numbers: NGC 4486, UGC 7654, Arp 152 and 3C 274. While these are meaningful to astronomers, they don’t exactly spark the imagination like the names of planets, moons, asteroids, comets and other cosmic objects that recall gods or other figures from ancient mythologies.

Why do some celestial objects get evocative, mythic names, while black holes — arguably among the most mysterious and exciting of all cosmic phenomena — typically don’t?

Official recognition

For any space object’s name to be officially recognized by astronomers around the world, the moniker first has to be approved by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), astronomer Morgan Hollis, a spokesperson for the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) in the United Kingdom, told Live Science in an email.

Founded in 1919, the IAU established naming systems “so that objects can be unambiguously identified and everyone knows exactly which object is being talked about in a given research paper,” Hollis said.

But while these conventions exist for stars, planets, asteroids and the like, no such protocols are in place yet for black holes. This is partly because they haven’t been directly observable until now, according to Hollis.

“Plenty of theoretical studies have been done of course, but information was limited about specific black holes, and so naming wasn’t really an issue,” he said.

Only a number

Before the formation of the IAU, many objects in space became widely known as numbers in catalogs created by astronomers such as Charles Messier, who lived in France during the late 18th century and early 19th century. Messier and others documented their observations and numbered objects sequentially, and other astronomers started referring to those objects by their catalog numbers, said Vincent Fish, a research scientist at Haystack Observatory at MIT in Boston, and part of the team that imaged the M87 black hole.

Messier’s catalog, published in 1771, contains 110 objects; 87th in the list is the galaxy M87. But other catalogs exist alongside Messier’s, and many of their observations overlap, so the same galaxy — and the same black hole — can have multiple names, Fish told Live Science.

“It can be complicated sometimes when you know a source [of emissions] by one name and someone knows it by a different name, and it takes a while to figure out you’re talking about the same source,” he explained.

The M87 black hole, however, was already so well-known that the EHT team at Haystack Observatory simply referred to it as “M87,” or occasionally “3C 274” (they did not have a special nickname for it, Fish said).

What’s in a name?

Over time, observations by more sensitive satellites swelled the ranks of suspected black holes; those that didn’t have catalog names were usually referred to by their coordinates in space — “essentially, its celestial longitude and latitude” — known as the right ascension and declination, Michael Shara, a curator and professor with the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, told Live Science.

Those coordinate “names” also include a few letters at the beginning to show which satellite located the black hole, Shara said. And for now, that’s the most practical approach for identification, as there are millions of X-ray sources that could represent supermassive black holes, he said.

However, there’s certainly precedent for celestial objects acquiring more evocative names in addition to astronomers’ letters and numbers, according to Fish. For example, the galaxy M104 is commonly known as the Sombrero Galaxy, for its resemblance to a wide-brimmed hat, while the nebula Barnard 3’s horse-like appearance lent it the name Horsehead Nebula, he said.

Perhaps now that EHT has proved that directly imaging a black hole is possible, it may be time for the global community of astronomers to collectively reconsider how black holes will be named moving forward, Shara said.

However, even if Pōwehi does begin to catch on as the M87 black hole’s new name, it won’t be considered official without the recognition of the IAU, according to Shara.

“If it’s to ‘stick,’ it’ll require IAU backing — but I think it’s got a good chance, as two of the radio telescopes involved in the work are based in Hawaii,” Shara said.

As an official name, Pōwehi would honor not only key instruments involved in the achievement, but also “the scientists and local community who all work together and help to make such groundbreaking scientific endeavors possible,” Hollis said.

“The eventual name will no doubt be decided by consensus in the scientific literature, if the IAU don’t step in,” he added. “We’ll have to wait and see.”