For NASA’s Kepler space telescope, the world will end in ice rather than fire.

Kepler, which is responsible for 70 percent of the roughly 3,800 confirmed exoplanet discoveries to date, has closed its powerful eyes. The prolific telescope is out of fuel and will be decommissioned in the next week or two, NASA officials announced yesterday (Oct. 30).

Kepler will not go out in a dramatic blaze of glory like NASA’s Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft, which was intentionally deorbited into the ringed planet’s thick atmosphere in September 2017 when its fuel gauge began scraping “E.”

Rather, Kepler team members will beam a single, simple command to the sun-orbiting planet hunter, triggering a decommissioning sequence that’s already aboard the spacecraft. Kepler will shut down its radio transmitter and onboard fault-protection systems, becoming an inert chunk of metal that floats, silent and unresponding, through the cold, dark depths of space.

“Kepler is currently trailing the Earth by about 94 million miles, and will remain the same distance from the Earth for the foreseeable future,” Charlie Sobeck, project system engineer at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, said during a teleconference with reporters yesterday.

There will be some jostling over the decades. By 2060, for example, the faster-orbiting Earth will have almost caught up with Kepler, NASA officials explained in a new video. Our planet’s gravity will then nudge the space telescope toward the sun a bit, and Kepler will move ahead of Earth on a slightly shorter, faster orbit. But in 2117, Kepler will pop back onto its old path after another encounter with Earth. And the cycle will continue.

So a rescue or refueling mission would be nearly impossible, NASA officials have said. Astronauts repaired and upgraded the agency’s Hubble Space Telescope five separate times from 1993 to 2009, but Hubble resides in low-Earth orbit, a mere 353 miles (569 kilometers) above our planet.

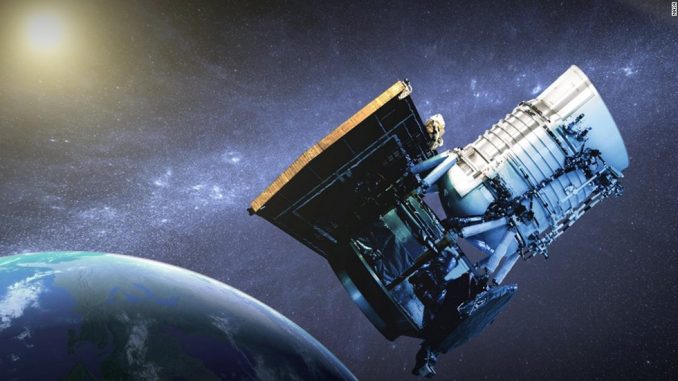

Kepler launched in March 2009, tasked with determining how common Earth-like planets are around the Milky Way galaxy. The spacecraft hunted for alien worlds using the “transit method,” noting the tiny dips in stars’ brightness caused by orbiting planets crossing their faces.

Kepler initially stared at about 150,000 stars simultaneously. This original work came to an end in May 2013, when the spacecraft lost the second of its four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels. However, mission team members soon figured out that they could stabilize Kepler using the remaining wheels and sunlight pressure, and in 2014 the scope embarked on a new mission known as K2.

During K2, Kepler made a variety of observations over shifting 80-day campaigns, studying everything from asteroids and comets in our own solar system to distant supernova explosions.

But Kepler will forever be remembered for its exoplanet finds. The spacecraft’s current tally stands at 2,681 alien worlds, 354 of which were discovered during K2. Nearly 2,900 Kepler exoplanet “candidates” still await vetting by follow-up analysis or observation, and history suggests that most of them will end up being confirmed.

Kepler has long been about far more than just those raw numbers, however. The space telescope’s observations have revealed that planets outnumber stars in the galaxy; that Earth-like, potentially habitable worlds are common; and that planets, and planetary systems, are far more varied and diverse than the limited example provided by our own solar system.

Such discoveries are reshaping astronomers’ understanding of humanity’s place in the universe and better equipping astrobiologists to search for signs of our cosmic neighbors, mission team members said.

“Basically, Kepler opened the gate for mankind’s exploration of the cosmos,” Kepler mission founding principal investigator Bill Borucki, who retired in 2015 after many years at NASA Ames, said during yesterday’s telecon.

The total price tag for Kepler will end up being about $700 million, Sobeck and Borucki said.